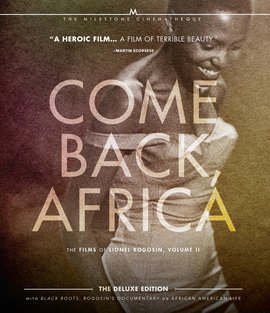

Come

Back, Africa: The Films Of Lionel Rogosin, Volume II

(1959 - 1970/Milestone Blu-ray)

Picture:

Come

Back, Africa:

A; Black

Roots:

B- Sound: Come

Back, Africa:

A; Black

Roots:

C Extras: A Films: A

Apartheid

in South Africa officially ended in 1994, and yet 20-plus years later

it's impossible to watch Come

Back, Africa,

Lionel Rogosin's 1959 docu-narrative of the nation and its

institutionalized racism, as a dispatch from the long-ago past.

Rather, it's as urgent in its outrage, disgust, and activism today as

it was more than 55 years ago.

After

shooting On

the Bowery

(reviewed elsewhere on this site), a film concerned with the

disregard toward and disposability of New York's homeless population,

Rogosin turned his attention to South Africa's decade-old policy of

apartheid. It was a topic perfect for a filmmaker whose

social-justice streak was many miles long: National race-based

policies aimed at grinding its black population into dust through

inhumane treatment, savage segregation, and an unending barrage of

everyday indignities.

Like

his previous feature, Rogosin made Come

Back, Africa

on location using non-professional actors. In this case, we follow

Zachariah, a laborer from the country who dreams of working in the

city and providing a better life for, and with, his wife and

children. He bounces from one job to the next and confronts

increasingly despicable treatment, from both whites and blacks. The

experience Zachariah has with whites is brutal. When he lands a

domestic job, for example, the woman of the house changes his name to

Jack, complains about him to her husband as if he's not there (even

though he's standing next to her), her husband waves the complaints

away saying ''He's only a native,'' and when the wife refers to

Zachariah disparagingly as a 'native' she spits the word out like its

poison, before graduating to screaming ''savage'' at him. As the

film progresses, Zachariah is fired from one job after another over

seemingly inconsequential offenses, threatened with expulsion from

the city, and finally arrested in the middle of the night without

cause.

But

as nasty as these experiences are, Zachariah finds little quarter

from members of his own community. He has a group of friends he

leans on when times are tough, but they barely protect him from a

local thug who, after a perceived slight, tries to stab Zachariah in

the street. Later, he murders Zachariah's wife when Zach's in jail.

The final moments of the film, Zachariah howling over his wife's

body, are searing, full of anguish and anger, the full force of the

oppression of whites and the dehumanizing consequences for blacks

exploding through one man's inconceivable grief. It haunts your

memory forever.

That

raw emotion can't compensate for how blunt Come

Back, Africa

can be, both in terms of content and filmmaking. You never question

what a character's motivation is or where Rogosin's sympathies lie,

whereas On

the Bowery

had more shades of gray. Still, Come

Back, Africa

is a more emotionally visceral film thanks in no small part to being

shot on location. On

the Bowery

was shot on the actual Bowery, but the threat to Rogosin was minimal.

Not so with his second feature. He couldn't walk into South Africa

and get permission from the government to shoot a full-bore

condemnation of its inhumane treatment of its black population. So

he told officials he was in country to make a ''political-neutral

musical travelogue.'' He shot footage surreptitiously to avoid

censors, then had the material smuggled out of the country. This

gives the film a heightened sense of verite, especially in the street

scenes and in those harrowing moments of Zach confronting a

constantly shifting day-to-day reality of life in South Africa.

(While

the film is decidedly not apolitical, there are some elements of the

travelogue. There are two segments in the middle of the film where

Rogosin luxuriates on local musical expression. The first documents

life in the slum, from faces young and old to shops and gatherings of

residents, as a group of local kids play flute-like instruments. The

second captures those kids performing for white office workers and

shoppers, who look on with curiosity, impatience, and sometimes

enthusiasm. Police officers watch menacingly, but seem OK with

allowing the kids to scratch out some loose change. These scenes are

brilliant inclusions, not only as impressions of everyday life in

South Africa in 1958/9, but as records of a culture in the process of

being systemically marginalized - and possibly destroyed - by

apartheid.)

The

film is a testament to the ingenuity of Rogosin, one of America's

most undeservedly forgotten filmmakers. (His work influenced John

Cassavetes, was a touchstone for Martin Scorsese, and echoes in the

films of Errol Morris and Alex Gibney.) He took the experience of

making On

the Bowery,

honed it, sharpened it, and pointed it at the heart of one of the

most repressively racist nations in history. Come

Back, Africa

is a primal scream of outrage that Rogosin hoped would spur the world

to reject South Africa's policies and put an end to apartheid before

lasting damage could be done. We know now that the film didn't have

that effect; apartheid would last another 35 years.

But

that doesn't diminish how successful the film is as a piece of

activism. Rogosin risked his life, and the lives of his actors and

crew, to steal an unsparing glimpse into a society collapsing in on

itself thanks to racism run rampant. But Come

Back, Africa

isn't just about a society halfway around the world. The film's

about us, too. It's impossible that Rogosin didn't think he'd also

affect America's seemingly intractable apartheid, Jim Crow, and its

less talked about but no-less-significant analogues in the north. By

presenting so much cruelty and so much hatred - all of it stemming

from racism - Americans couldn't help but demand change at home.

Of

course, that effort failed, too. Accordingly, watching Come

Back, Africa

today, is still a troubling experience. Only the heartless will be

unmoved by Zachariah's arc, but it's also impossible to not dwell on

the everyday indignities, not-so-coded rhetoric, and blatant

segregation suffered by minorities based on race, gender, religion,

and sexual orientation that continues to fester around the world.

From stop-and-frisk and challenging Barack Obama's birthplace in the

United States to race-based legislation aimed at expelled Haitians

from the Dominican Republic to the rise of ISIS in the Middle East,

systemic discrimination endures, seemingly more intractable than ever

before.

Like

with On

the Bowery,

though, Come

Back, Africa

is an invaluable document of an era we'd all like to think we've

progressed beyond. And while the realities of our present can be

thoroughly discouraging, it gives Rogosin's work a different legacy

than the one he hoped for a half century ago, one that is potentially

more valuable than activism - memory. Rogosin has preserved some of

our worst societal ills in an effort to, on the one hand, eradicate

them, and on the other to remind us that the work is never done.

Maybe it can never be complete. But his documentaries are challenges

that we cannot ignore. Fifty years on, they continue to speak truth

to power, to guide us forward, and encourage us that we can affect

change - if we really want it.

Milestone

Films' efforts in bringing Rogosin's work to wider attention is one

of the great accomplishments of the Blu-ray era. Volume

I,

which included On

the Bowery,

is a majestic set; Volume

II is

just as superlative.

Besides

Come

Back, Africa,

the two-disc set includes a second feature, Black

Roots,

which even more explicitly links activism with memory.

African-American writers, musicians, activists, and leaders talk

about the black experience in America with blistering honesty and in

sometimes harrowing detail. Shot Charlie Rose-style for European

public television in 1970, with one person, two people, or a small

group on a dark set, the film is an incredible act of preservation

that could easily have carried a home video release on its own. To

that end, Milestone gives it its own disc to breathe. Disc 2

includes Black

Roots

and a 27-minute making-of feature. Also included is the 74-minute

documentary Have

You Seen Drum Recently?,

a 1989 film that captures the importance (socially, culturally, and

politically) of the South African magazine Drum,

which catered to an urban black readership during apartheid.

Come Back, Africa

gets all of Disc 1. Besides the film, there's a 64-minute making of

documentary An

American in Sophiatown,

an audio interview Rogosin did with United Nations radio in 1978

about what he hoped to accomplish with the film and how like South

Africa is to end apartheid, an introduction by Martin Scorsese, and a

trailer. It's hard to think what else could be added to either disc.

Every extra is valuable and adds context and understanding to who

Rogosin was as a filmmaker and person.

On the technical side,

Come

Back, Africa

is given an amazing visual presentation. It went through a 2K

restoration in 2005, which is the source for the disc. It's hard to

imagine it ever looked as good as it does today. (Previously, the

film has been passed from college campus to film society, which isn't

the ideal condition for preserving print quality.) That said, there

are some points in the film where frames are missing or it's a bit

soft. Those are so few and far between, though, that they by no

means impair the experience. Black

Roots

is a different story. The print is in much rougher shape. It's a

poorly lit film made for public TV, and it looks about how that

sounds. It doesn't diminish the value of the film itself, but it

does at times make it a challenge to watch. Both are roughly

presented in 1.33 X 1 1080p digital High Definition presentations.

Audio-wise,

the same breakdown exists. Come

Back, Africa

has a PCM Mono soundtrack, which does its job without much pop or

hiss. There's an occasional warble, but, again, it doesn't impair

anything. Black

Roots,

meanwhile, is a little tougher to hear. Mic placement, especially in

the larger group scenes, might have been an issue - single-person

interviews are fine, but the more people (and elements, like guitars)

are added, the audio gets more and more strained.

That

said, we're extraordinarily lucky to have this work preserved in

digital form. Any quibbles with the presentation are minor compared

to the alternative: this work committed to oblivion.

-

Dante A. Ciampaglia