Project

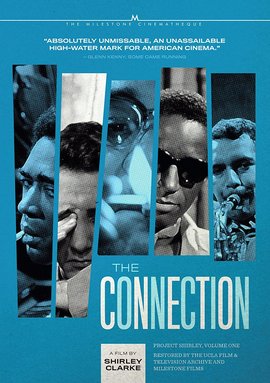

Shirley Volumes 1-3: The Connection

(1961), Portrait

of Jason

(1967), Ornette:

Made in America

(1985/Milestone Films Blu-rays/separate releases)

The

Connection

Picture:

A Sound: A Extras: B+ Film: A-

Portrait

of Jason

Picture:

B+ Sound: B Extras: B Film: B

Ornette:

Made in America

Picture:

B- Sound: B Extras: B Film: B

Milestone

Films is doing God's work, cinematically speaking. From resurrecting

I Am Cuba in 1995 to resuscitating Charles Burns' unassailable

American classic Killer of Sheep in 2007 to restoring Lionel

Rogosin essential filmography beginning with the 2011 rerelease of On

the Bowery, Amy Heller and Dennis Doros have filled crucial gaps

in not only the independent canon but, as importantly, the home video

market. So many of the films included in the Milestone catalog - The

Exiles, Losing Ground, Come Back, Africa, The

Daughter of Dawn, Strange Victory, In the Land of

Headhunters, My Brother's Wedding - are works that have

been forgotten or ignored, created by filmmakers who are

underrepresented or marginalized, about people and communities and

cultures that exist at or have been pushed to the periphery of

mainstream experience. There is clearly an obsession at play here -

one that should be celebrated - to reclaim the documentary evidence

of lives, true and otherwise, that discarded by an ever more

homogenous cinema, one that borders on monoculture.

It's

that obsessive nature that led Milestone eight years ago to embark on

the ambitious task of restoring the work of pioneering filmmaker

Shirley Clarke. Called Project Shirley, it includes four

volumes of features, shorts, outtakes, documents, behind-the-scenes

footage, interviews, trailers, and other ephemera. These are

collected in The Connection: Project Shirley Vol. 1, Portrait

of Jason: Project Shirley Vol. 2, Ornette: Made in America -

Project Shirley Vol. 3, and The Magic Box: Project Shirley

Vol. 4. Taken together, they chart the most complete course of

Clarke's career ever assembled (a claim Milestone will likely hold

forever), from her first feature, the proto-fauxumentary The

Connection released in 1961, to her final film, the actual

documentary Ornette: Made in America released in 1985. In

all, Clarke only made five features - the other three are The Cool

World and Robert Frost: A Lover's Quarrel with the World

from 1963 and 1967's Portrait of Jason - and Milestone has

released four of them. (The lone exception is The Cool World.)

The rest of her oeuvre is comprised of shorts: about dance, about

people, about place.

THE

CONNECTION

Born

in 1919, Clarke began her career as a dancer, where she had limited

success as choreographer. That led her to move to film. She studied

with Hans Richter and soon became a fixture of New York's avant-garde

arts scene in the 1950s. She was part of a circle that included

filmmakers like Jonas Mekas, Lionel Rogosin, D. A. Pennebaker, and

Stan Brakhage, and that overlapped with the kind of experimental

performance happening at the Living Theater. (It should also be

noted her sister is Elaine Dundy, the author of the fantastic and

criminally overlooked The Dud Avocado, which is available from NYRB

Classics.)

It

was at the Living Theater where Clarke encountered The Connection,

Jack Gelber's 1959 play notorious among the anti-obscenity-driven

conformity of New York's mainstream art world. The jazz-infused

work, constructed as a window onto a group of junkies waiting in a

grungy apartment for their connection to arrive with a batch of

heroin, was rife with vulgar language and populated with gritty

characters whose lives and experiences exist outside the narrow view

of polite society. The framing device was also novel: A theater

producer wants to stage a play about addicts, so he invades these

characters' lives for research because he wants to use real addicts.

That led to the titillation that attracted viewers, an

is-it-or-isn't-it-real moment of someone shooting up on stage. That

blurring of lines between reality and fantasy extended beyond the

stage, too. The actors, still in character, would approach audience

members in the lobby during intermission begging for money and

berating them as hypocrites.

The

Connection was shocking. It was beyond the pale. And it ran for

more than 700 performances, picking up numerous Obie awards on the

way. Naturally there was interest in making a film version, and

Clarke saw the play as a way to interrogate cinema verite and the

blurring of lines between reality and fiction. So the film version

of The Connection became a kind of found-footage documentary

about a filmmaker, Jim Dunn (William Redfield) and his cameraman J.J.

(Roscoe Browne), trying to make a documentary about junkies. What we

see was assembled by J.J. after Jim gets too close to his subjects,

who goad him into trying heroin. It messes with the pretentious

young man's clean mind, and the user becomes the used - in more ways

than one.

Written

by Gelber, The Connection is bound to a single set: the

run-down apartment of a guy named Leach (Warren Finnerty, who looks

and sounds like a cross between Steve Buscemi and Willem Dafoe), who

repeatedly harangues his fellow junkies that they're ruining his

well-appointed palace. ''I live comfortable,'' he says to the

audience early on. ''I'm no junkie bum. Look at my pad. It's

clean.'' (It's decidedly not clean, as evidenced by the mounds of

junk and detritus piled up in the corners and the cockroach crawling

up a wall.) There are numerous moments of this kind of direct

address throughout the film, which not only recreates the theatrical

experience in the cinematic mode but also shakes us out of our

position as passive, complacent consumers.

In

one particularly memorable example, Solly (Jerome Raphael), a jovial,

overweight corner philosopher in need of a wash and new set of

clothes, grabs us by the lapels and confronts us about what we hope

to find by watching them: ''What do you want to hear? That we're a

petty, self-annihilating microcosm? That's what you want to hear.

Dope fiends! Hurry, hurry, hurry the circus is here! Suicide is not

uncommon among us. The overdose of heroin is when the final line of

life and death surges in a silent breeze of ecstatic summer. Who

else can make so much of passing out? Who else can make so much out

of passing out? But existence on another plane, whether to alleviate

the suffering of this one or to wish for death? It doesn't matter...

Eh, I hate oversimplifications....''

It's

Clarke's commitment to eviscerating not just the fourth wall but the

safe space afforded the audience by sitting in a theater, at a

seeming spatial and dimensional remove from what's on screen, is

total. And The Connection is subvertly dense and exquisite as

a result. There are all sorts of issues about racial dynamics at

play: Jim, a white filmmaker, constantly shoves his camera in the

faces of not-having-it black jazz musicians rehearsing in the

apartment; his cameraman, also black, is reduced to a mostly-faceless

subservient role; but the connection, Cowboy (Carl Lee), who is

black, is ultimately the one in control. (And then there are the

related confrontations with class and power.) The film is

exquisitely shot, from intense close-ups that evoke photographers

like Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, and W. Eugene Smith, to people in

environments that recall the best mid-century photojournalists.

Clarke and cinematographer Arthur J. Ornitz (who later shot Serpico)

capture these hollowed out people as stand-ins for those beginning to

actually be left behind by the postwar American machine hollowing out

cities in its promotion of white flight to the suburbs.

Without

qualification, The Connection is a masterpiece - the kind of

film that speaks to its moment, still reverberates more than a half

century later, and will continue to resound as long people watch

movies. Not only is it a technical and narrative accomplishment, it

works at something more interior, as Jonas Mekas articulated in a

1962 ''Movie Journal'' column for the Village Voice: ''This film

(like the play), this moody, suffering new art, really is not a

forecast of disaster, but a joyous sign that there is a deep despair

going on somewhere in us - that not everything is so air-conditioned

(as we used to say) and dead in man - for we know that the deeper our

despair, the closer we are to the truth, to the way out. The

Connection, thus - like most of the new 'nihilistic,' 'dadaist,'

'escapist,' etc., art - is a positive art, one which doesn't lie or

fake or pretend about ourselves. It reaches beyond the naturalistic,

pragmatic, surface art and shows something of the essence.''

PORTRAIT

OF JASON

That

attitude would continue to be Clarke's ethos as a filmmaker

throughout her career - and Portrait of Jason might be the

apotheosis of it. Shot over a 12-hour period (9 p.m. to 9 a.m.) on

December 3, 1966, in Clarke's apartment, the film is a one-man

performance piece with maybe the most unreliable subject of all time.

In essence, Clarke turned her camera on and let Jason Holliday (born

Aaron Paine) do his ''thing,'' as she described it in 1967. What

that thing is, it seems, is regaling us, the off-screen Clarke and

Carl Lee, and whoever stops to listen with stories about his life and

judgments of people he has encountered. But more to the point, it

allowed Clarke the ultimate opportunity to challenge the boundaries

of cinema verite. ''We have rarely allowed anyone to speak for

himself for more than a few minutes at a time,'' she told Mekas in

1967. ''Just imagine what might happen if someone was given his head

and allowed to let go for many consecutive hours. I was curious, and

wow! did I find out.''

Jason

is a gay black man in 1960s America, a ''stone-cold'' hustler,

performer, and a kind of raconteur with dreams of mounting an

autobiographical cabaret show charting his journey from getting

''hung up being a house boy'' to studying acting with Charles

Laughton and dance with Martha Graham to whatever is happening the

moment he's on the stage. He also has a reputation with Clarke, Lee,

and others in that group as being duplicitous and, it seems downright

hurtful. At one point, he recalls how he squeezes friends and family

- some over and over again - for money to fund his as-yet-conceptual

show. ''If they went for it once, if you wait long enough and go

back again...'' he says, all but calling this well meaning folks

suckers. Earlier on in the film, he says, ''I go out of my way to

unglue people.''

But

in a way Portrait of Jason is a way for Clarke to unglue her

subject. ''I suspected that for all his cleverness his lack of the

know-how of film-making would prevent him from being able to control

his own image of himself,'' she told Mekas. Shot almost like a TV

show, with focus cuts between vignettes and stories acting like

segues into and out of commercial breaks, the film feels like kind of

news program of its era - an expose of this man who stands as a

microcosm of a subculture. Jason is seated at a quarter turn,

smoking and drinking, answering questions that might as well be

coming from Edward R. Murrow as Shirley Clarke. But what we get is

far more raw than what you'd get from CBS. The film is highly

destabilizing in its honesty; Jason's stories can get intimate and

intense.

Yet

there's an off quality to the way the evening is managed. In the

course of the shoot, Jason drinks - and drinks and drinks and drinks

- and as he seems to get progressively more sloshed his guard slips

and drops. And as the night wears on, his shifts between being on

and off become more dramatic. He'll gesticulate and beam

gregariously through a story, and when it's over his eyes seem to go

distant and somber before someone off-camera says ''Tells us

about...,'' and Jason is back on.

It's

easy to view this as Clarke and her crew using Jason for some

cinematic experiment. But in fact the reality is more complicated:

they were using each other, and the resulting film - not quite a

documentary, not quite a performance piece - is a kind of therapeutic

bloodletting. Again, from Clarke's 1967 interview with Mekas:

''One

thing I never expected was the highly charged emotional evening that

took place. I discovered the antagonisms I'd been suppressing about

Jason. I was indeed emotionally involved. Since the readers of this

'conversation' haven't yet seen the film, I should say here that

while Jason spoke to the camera, other people were in the room,

during the shooting, besides myself, who reacted to what Jason said

and did, got involved with him. We have a tiny crew, plus two old

friends of Jason who knew all his bits and had suffered from his

endless machinations as well as enjoyed his fun and games.

''How

the people behind the camera reacted that night is a very important

part of what the film is about. Little did I expect how much of

ourselves we would reveal as the night progressed. Originally I had

planned that you would see and hear only Jason, but when I saw the

rushes I knew the real story of what happened that night in my living

room had to include all of us, and so our question-reaction probes,

our irritations and angers, as well as our laughter remain part of

the film, essential to the reality of one winter's night in 1966

spent with one Jason Holliday, ne Aaron Paine.''

The

result, then, is this odd and authentic document - partly of a

friendship, but more importantly of life as a gay black man in New

York City in the 1960s. There are undoubtedly questions about how

much of what Jason says is part of his direct experience, how much

was embellished or made up, and how much was appropriated from

others. But the reality is that these things did happen, and to have

that voice and that world preserved in this way is beyond invaluable.

ORNETTE:

MADE IN AMERICA

The

same can be said for what Clarke collects in her final film, Ornette:

Made in America. Ornette Coleman, one of the defining jazz

musicians of the 20th century, plotted a course from the bop era to

the more experimental, funk-infused music that would emerge in the

late 1960s through the 1980s with his seminal 1959 album, The Shape

of Jazz to Come. Clarke's history with Coleman dates back to the

1960s, and the documentary leverages that to not only track his

development as an musician but excavate the interior life of a unique

artist.

The

film is loosely framed around Coleman's 1983 return to Ft. Worth,

Texas, where he grew up in a segregated slum, to premiere his

jazz-classical composition Skies of America with the Ft. Worth

Symphony. But on those bones, Clarke hangs vignettes of Coleman's

days as a kid in Texas through reenactments; rehearsal and interview

footage shot by Clarke in New York City in the late '60s; traditional

talking-head interviews with painters and critics and other

musicians, like his son (and the drummer in his band) Sabir Kamal;

and monologues from Coleman himself about where his creative impulse

originates.

One

of the bigger influences that emerges is architect and theorist

Buckminster Fuller, who Coleman calls ''probably my best hero. ''In

the film, he recalls being inspired during a Fuller lecture he

attended as a student at Hollywood High School. Coleman thought he'd

be an architect, before turning to music. And in Fuller he found a

kindred spirit. ''The one thing that just really blew me away was

his demonstration of his own domes,'' Coleman says. ''And when he

demonstrated how his domes are put together and how geometric they

were done, it just blew me away because I said, 'This is how I've

been writing music!' '' It's unsurprising to learn that Coleman,

whose music is way more angular and geometrical than someone like

John Coltrane, would find inspiration in someone as creatively

progressive as Buckminster Fuller. But his viewpoint and ideas -

particularly on imagination - continued to influence Coleman as he

continued to refine his personality as an artist. ''The expression

of all individual imagination is what I call 'harmolotics,' '' he

says. ''And each being's imagination has its own vision. And there

are as many visions as there are stars in the sky.'' It's a fitting

sentiment - not only for Coleman's iconoclastic work but Clarke's, as

well.

In

many ways, Ornette: Made in America is Clarke's most

conventional film. She bounces around between all the different

elements she uses to reconstruct (and articulate) Coleman's

experience, but the end result is a pretty straightforward narrative.

Yet it's still infused with the restless, probing spirit endemic to

all of Clarke's work - as well as the beautiful dissonance of an

Ornette Coleman composition - that she uses to investigate not only

an individual or group but the contours of national culture and

identity. So it's appropriate she used Skies of America to frame

Coleman's life. A man who pulled himself out of crushing poverty to

become one of the world's premiere musicians and artists, not in some

direct line from A to B but via a looping path of experimentation and

success and failure and acceptance, while navigating the fault lines

of race - that's the kind of story that was once emblematic of the

''American Dream.'' But in 1985, at the start of the Reagan era, it

felt like the dream was slipping away, which adds an elegiac note to

the film.

And,

ultimately, it became the final Clarke's final cinematic statement.

She died in 1997, and while Ornette was released 12 years

earlier it is a fitting coda to a career that began with The

Connection, a film that forced confrontation with the first

cracks in that receding American promise.

PROJECT

SHIRLEY DISC EXTRAS AND TECHNICAL THOUGHTS

The

first three volumes of Shirley Clarke films are each one disc sets,

but they are all loaded with extras. The Connection includes:

''The Connection Home Movies,'' six minutes of black-and-white

behind-the-scenes footage; ''A Conversation with Albert Brenner,'' a

four-minute reminiscence by the production designer of the film;

''Connecting with Freddie Redd,'' a 27-minute interview with the lead

musician in the film; a 29-minute radio interview with Clarke from

1959; the four-minute short ''Carl and Max at the Chelsea;'' two

marketing songs from 1964; a photo gallery, and the trailer.

Portrait of Jason includes: ''The Lost Confrontation,'' a

seven-minute bit that was cut from the film; the 25-minute

documentary short ''Where's Shirley;'' a three-minute short from

1967, ''Butterfly;'' a 53-minute interview with Clarke from 1967; a

54-minute audio-only piece ''The Jason Holliday Comedy Album;'' a

nine-and-a-half-minute episode of Underground New York from 1967 that

focuses on Clarke; 35 minutes of audio outtakes; color footage of

Jason; a restoration demonstration; and a trailer. Ornette: Made

in America includes: radio and video interviews with Clarke;

''The Link Revisited,'' a short documentary about the club featured

in the film; the short ''Shirley Loves Felix;'' a trailer; and a

booklet with an essay by producer Kathelin Hoffman Gray.

Overall,

the extras on the discs are exceptional. But where there's a glaring

soft spot is on Portrait of Jason. Of the three films, this

is the one that demands the most context. The relationship and

dynamic between Clarke and Jason is fraught, and their backstory

helps explain a lot about what is going on in what we're seeing.

Without it, you have a feeling of being unmoored in this cinematic

sea. And, frankly, it can be unpleasant. As noted above, there is a

definite feeling of one party exploiting another the first time

around.

After

watching the film, I worked through the extras hoping to find

something to help make sense of what I had just seen - not the actual

footage, but the emotional and interpersonal dynamics at work - but I

came up mostly empty. It was only in doing my own research that I

was able to find more to help fill in the gaps. Once I did, the film

became increasingly nuanced. What I had originally seen as

exploitative, for example, turned out to be far more complex and

faceted. There is certainly a lot to glean from the film on its own

- again, as a document of the experience of a gay black man in the

1960s, the film is unimpeachable - but it does feel like a missed

opportunity to give viewers the fullest portrait of Clarke at this

particular moment.

When

it comes to the technical presentation, The Connection and

Portrait of Jason discs both feature restored prints and they

look incredible. The tonal depths and clarity of detail in The

Connection (1080p monochrome 1.33 X 1 with PCM Mono) is

especially beautiful. There's a lot going on in Leach's apartment,

and it's all crisp and clear. The crisp blacks and subtle grays in

the cinematography bring out everything that's happening in Leach's

apartment. And there's a lot, from paint peeling off falls to bits

of debris caught on shirts and in hair. At the start of the film,

Leach wears a black blazer over his plaid button-down. In one shot,

the light catches a pattern in the jacket that, frankly, is

impossible to believe could be visible in a print of a low-budget

independent film made 55 years ago. But there it is, yet that's how

good film stock (16mm or 35mm) could be at the time, and it's

gorgeous. Portrait of Jason (1080p monochrome 1.33 X 1 with

PCM Mono), meanwhile, looks light years better than it ever has (at

least based on the restoration demonstration). Clarke's apartment

isn't as visually interesting as the set in The Connection, so

it's easy for things to feel flat and lifeless. And indeed it was in

previous prints. But now, there's a sense of scale and scope in the

space, image focus has been improved, and flecks of cigarette ash and

details in Jason's wardrobe pop against his dark sportcoat. Ornette:

Made in America (1080p 1.78 X 1 (footage from various periods)

with PCM 2.0 Stereo) looks the shaggiest of the three, but that's not

an indictment. While it's a bit grainer than the other two films, it

adds a certain beamed-from-another-dimension quality that absolutely

works given the subject of the documentary. Audio-wise, the discs

get the job done. None of the three films were made to blow the

doors off a theater, and they don't. But dialogue is clean and

clear, and in the case of The Connection and Ornette,

the musical moments are rich and textured.

Milestone's

Project Shirley is a staggering achievement. Not only is it a

nearly-complete accounting of one of America's most important

independent filmmakers (the lack of The Cool World in any of

the volumes is impossible to overlook), it's a dynamic and vital

document of an era of American filmmaking that should be on a

cultural endangered-species list. As streaming services and home

video producers increasingly prioritize hits, name recognition, and

guaranteed money makers over smaller or lesser-known titles and

commercial failures, and as more and more films get locked away in

vaults to be forgotten or deteriorate into dust, it is more necessary

than ever to fight for and proactively guard our underground,

experimental, marginal, independent, avant-garde tradition. With its

work on Shirley Clarke's legacy - as well as those of Lionel

Rogosin's and Charles Burns', among others - Milestone has

established itself as perhaps the premiere sentinels in this ongoing

fight.

-

Dante A. Ciampaglia