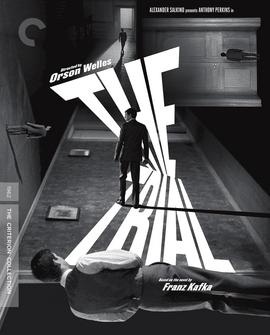

The

Trial

(1962/Orson Welles/Criterion 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray)

4K

Ultra HD Picture: B+ Picture (1080p Blu-ray): B Sound: B+

Extras: B+ Film: A

I

have a bit of an obsession with directors who find their groove and

tear off a sustained sequence of absolute, unimpeachable cinema art.

Francis Ford Coppola is - and probably always will be - at the top of

this list: The

Godfather

(1972), The

Conversation

(1974), The

Godfather Part II

(1974), and Apocalypse

Now

(1979); it's an inconceivably commanding, epic run of work. An

argument could be made for Stanley Kubrick at second place: Dr.

Strangelove

(1964), 2001:

A Space Odyssey

(1968), A

Clockwork Orange

(1971). (Maybe tack on Barry

Lyndon

(1975)?) Martin Scorsese makes a strong case too - Raging

Bull

(1980), The

King of Comedy

(1982), After

Hours

(1985) - except that the latter two are still cult, not mainstream,

classics. Steven Spielberg never had more than two back-to-back

triumphs. Ditto Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder and John Ford and

David Lynch. And on it goes.

An

unexpected challenger entered this conversation late in 2023. Orson

Welles' career is one defined by studio interference, backbreaking

budget constraints, and generally unrealized potential. But as the

years go on and cinema catches up with his genius, more of his work

is salvaged and reappraised. For decades, it seemed like the one-two

of Citizen

Kane

(1941) and The

Magnificent Ambersons

(1942), even in its butchered form, represented Welles at something

of a peak, with flashes of the old fire dotting the rest of his

career: A

Lady from Shanghai

here, a Chimes

at Midnight

there.

The

Trial

(1962), Welles' oft-maligned adaptation of Franz Kafka's novel, was

never one of those flashes; more like a gust of wind that snuffed out

the light. Previously available in terrible presentations marked by

muddled soundtracks and muddy visuals - when it could be seen at all

- it rarely reared its head in the conversation about Welles'

filmmaking. Indeed, even when Welles was alive, his most ardent

champion, Peter Bogdanovich, wrote it off as something like

worthless. Bogdanovich eventually came around after Welles urged him

to see it again (with Welles seated next to him), and Welles himself

often spoke about how the making of the film was his most joyous

experience as a filmmaker.

The

rest of us finally had a chance at a reawakening when a beautiful

digital 4K restoration of The

Trial

was released theatrically and then on disc by the Criterion

Collection. Suddenly here was this compelling, unnerving, baroque

noir that smashed together modernism and classicism and post-war

Europe and Cold War absurdity. Like Kafka, and the inane culture

that has made him prophetic, the film is dark and smudgy and

dangerous and hilarious and utterly contemporary.

There's

Josef K (Anthony Perkins), a middle-manager in his minimalist

Soviet-style apartment, believing he's destined to bigger things when

he's accused by some nameless person of some nameless crime and so is

forced to defend himself in some faceless system in front of a

faceless mob that moves in the ruins of an old world destroyed by a

long-ago war. There's the Advocate (Welles), an agent of this

bonkers system, who may or may not be able to help - everything's a

riddle to nowhere - and his sexy nurse/lover Leni (Romy Schneider),

who steals off with K for some extracurriculars in the thoroughly

ruined antechambers of the Advocate's lair. There's the court artist

(which court - the legal court, or a regal one?) Titorelli (William

Chappell), a Pop-inspired celebrity, based on the number of young

girls vying for his attention through the slats in his walls, who

meets K in his atelier and gives him nothing but more doubletalk.

Everything leads K in loop-de-loops - even his

execution-slash-suicide-slash-immolation. And it's all bookended by

pinscreen art of giant castle walls, with Welles reading Kafka's

short story ''Before the Law'' to start the film and adding some

narration to close it.

It's

a wonderfully esoteric, evocative film. (Pair with Scorsese's After

Hours

for a perfect double feature.) And it's not surprising it didn't

connect in 1962. Perkins is jumpy and wiry and, coming two years

after Psycho,

I imagine it was hard to shake Norman Bates from his visage. It's

still hard to do, 64 years after Hitchcock's masterpiece. The

cinematography is so specific - from its claustrophobic set-ups to

the night and interior scenes that are less black and white and more

a Frank Stella black-on-black painting on celluloid - that a bad

print would kill any chance of deciphering what's in front of you.

The physical landscape and locations are exceedingly dour, which

you'd expect from Yugoslavia and Eastern Europe at the start of the

1960s. And the audio can be a challenge, from the track itself,

which can sound like it's burbling out of some water, to the dubbing

of the non-English-speaking actors, which Welles himself did for many

of the parts.

The

restoration fixes most of the technical deficiencies - the audio is

still a challenge, but its uncanniness adds an exceptional dimension

to the film's overall sense of dislocation. And what we're presented

with is unquestionably one of Welles' great achievements. And it

comes in a sequence that should make us reconsider this period of his

career: Touch

of Evil

(1958), The

Trial

(1962), Chimes

at Midnight

(1965). Remarkable films, all, and the kind of daring,

boundary-pushing, paradigm-shifting work that, for a long time, we

were told Welles was incapable of after Kane,

or at least Ambersons.

There

has never been a question of Welles' importance to cinema, and while

each rediscovery confirms his place in the pantheon it also

complicates the easy narrative that has surrounded his career. Here

is an artist who didn't live hand-to-mouth, aborting film after film

and making bad commercials because he lost his muse. Instead, here

is a genius who was so far ahead of his time that the times didn't

know what to do with him, who was forced to scrounge for financing

and materials to capture as best he could (which was often not good

enough) the ideas and visions knocking around in his head.

This

is no great revelation in 2024. Only a stubborn fool would try to

discount Orson Welles as an overhyped wunderkind who never achieved

his potential. But what this revived The

Trial

does is decisively knock the legs out from under that argument. Here

is a great film made by a great filmmaker at the height of his

powers, in the midst of a creative burst nearly unparalleled by his

contemporaries or inheritors (in America at least). And in this

triptych of films, of which The

Trial

is the center panel, Welles gave us a view of the future of cinema.

It's only now that we're ready for what he had to show us.

Criterion's

4K edition of The

Trial

is an across-the-board upgrade from the film's previous home video

incarnations. Extras include a trailer; a wonderful and insightful

new commentary from historian/author Joseph McBride; and archival

interviews with Welles, Jeanne Moreau, who appears in a kind of

glorified cameo as K's sultry and mysterious neighbor, and

cinematographer Edmond Richard. There is also Filming

The Trial,

a 90-minute documentary consisting of Welles speaking with USC

students in 1981 after a screening of the film. In grand Wellesian

tradition, he originally intended to make a different documentary

about the making of the movie, with the Q&A as one part, but it

was never realized and the USC footage became the film. That's not

to undercut the discussion. It's great viewing, not only for Welles'

memories but because Welles was never better than in front of a live

audience. And here he's really in his element.

Technically,

the film looks and sounds as good as it likely ever will. But there

are a few caveats.

Regarding

the soundtrack, as mentioned above many of Welles' films -

particularly those shot in Europe - suffer from lackluster audio, for

all sorts of reasons. Here, is is presented in a PCM 1.0 Mono

(48kHz, 24-bit) lossless mix. Those issues are mitigated as best as

possible here, but there are still many moments where it sounds like

actors are physically in one space and speaking from another. It can

be distracting, though never so problematic that it ruins the

experience. (If memory serves, Chimes

at Midnight

has similar issues that really make parts of watching the film a

challenge.)

On

the visual side, there are similar moments of distraction. The first

comes at the start of the film, with K on his apartment balcony

speaking with the police. There's this strange static-like effect

that occurs on the ceiling of the balcony. It occurs on both the 4K

(2160p HEVC/H.265, 1.66 X 1, Ultra High Definition image with no HDR

of any kind) and Blu-ray discs, so it's clearly a result of the

restoration process. Is it fixable? Doubtful. But it's worth

noting. The other thing that can pull attention away is just how

deep the blacks can be. Characters in shadow can on occasion feel

like black cutouts on the screen (like the digital inserts Warners

added to Eyes

Wide Shut).

Again, this won't ruin the experience, just give you a sense of the

uncanny.

But

everything else is so gorgeous and fine that it's easy to forgive

these lapses - especially when you consider the state The Trial had

been in. I'll take some weird static and way-too-black missteps if

it means being able to, you know, accurately decipher the last shot

of the film - which you absolutely couldn't before.

-

Dante A. Ciampaglia